Building on the philosophy “Think Radical, Act Conservative,” Rob Lyon prepares for a low-water, cast-and-blast float through Oregon’s gorgeous Owyhee Canyon.

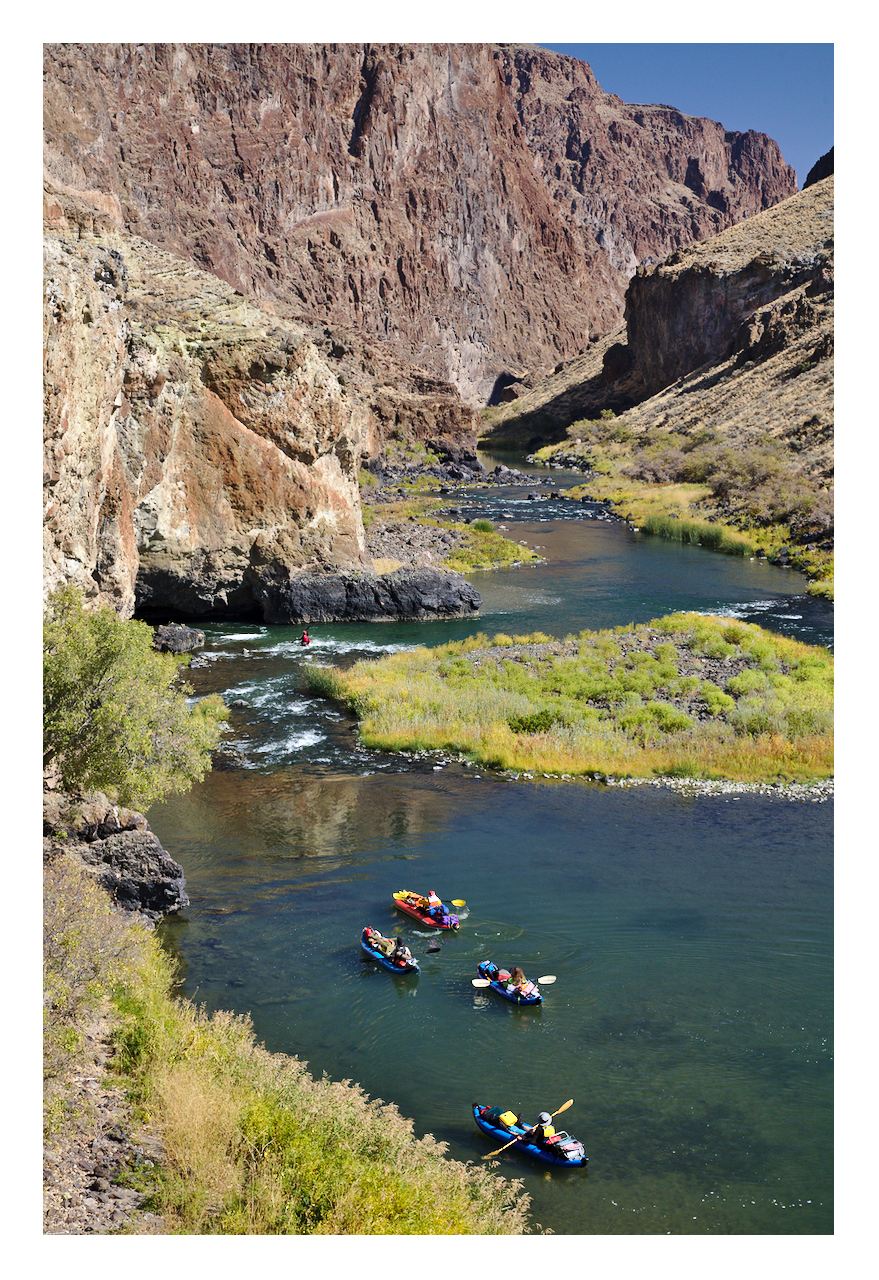

Thinking radically again this last October, a few friends and I ran a central portion of the Owyhee River Canyon. No doubt you’ve heard of the O’, carving through the lonely badlands of extreme southeastern Oregon. This stunningly beautiful canyon presents a mostly vertical panorama of pastel spires and hoodoos, palisades and basalt outcrops. A spring run in big water is on every gnarly river boater’s bucket list, but it is virtually left alone through summer and fall when the watershed shrinks like a tapped udder and the river flows a meager 100 cfs or less.

Talking with the caretaker at the BLM ranch at Birch Creek, he told us he sees maybe a single party each year come through in the fall. It is a different experience in the canyon, then. The river voice is relaxed instead of strident, yet it echoes the more loudly for lack of people.Scaled down to micro-rapids and long, reedy shallows, the river runs a steely green instead of mud brown. The nights are often icy, the days like balmy Indian summer, and the sumac and locust still have their leaves. It is the perfect time to settle in and live off the land. The plentiful chukar partridge are open game for the double barrel, and you have your choice of camps, with plenty of time to lay over for a couple of nights at your faves. Side canyons, broad sagebrush bowls and rocky rims beg to be explored. There’s no rush, just look at the river.

But like all radical wilderness endeavors in this crowded modern world, late-season Owyhee runs don’t come easily. Our October, 2012 trip marked our third fall visit to the canyon, and dialing in the O’ has definitely been a work in progress. We weren’t looking just to run the river; we wanted to spend some time in the canyon and let it all soak in. The trick with planning an extended fall trip is finding a boat big enough to haul the extra supplies and gear, yet nimble enough to slip through the tiny rock channels. It took us a couple of trips to get it right, and here’s a little history of how it went down.

When we showed up to return a canoe we’d rented, the shop owner took one look at the mutilated hull strapped to our rig and shook his head. We broke it, and we bought it.

In 2007, after making a scouting trip the year before, we ran two support canoes and three sea kayaks from Rome to Birch Creek – about fifty river miles. The canoes we absolutely destroyed. We had to strap one big Mad River together after the thwarts busted. And when we showed up to return a canoe we’d rented, the shop owner took one look at the mutilated hull strapped to our rig and shook his head. We broke it, and we bought it.

They canoes were bigger than they should have been, admittedly – too heavy and unwieldy in the rock gardens, and our one portage was a nightmare. A smaller canoe would have fared better. Fifty miles of humping those beasts through one rock garden after another left us no time to for anything else. The chukars had the last chuckle as they watched us float past with no time to stop and give chase. We were ready for a vacation by the time we were done, but we dug the daylights out of the canyon and vowed to come back.

So, back to the drawing board. Two years later, in 2009, we dropped into the canyon at an obscure launch point that would cut a good bit off our route. I had mixed feelings on this, remembering the bucolic float upriver through Jordan Valley – passing alongside cattle ranches and under old wooden bridges, then, as we neared the canyon proper, watching a dozen pheasant burst out of a grain field on river left, gliding in majestic single file overhead while a pair of English Setters pulled up short on the bluff, barking their displeasure. But the 20 miles we lopped off the original 50 gave us time to slow down and smell the canyon. What we got out of that trade was a traveling rhythm, that golden pace that provided as much shore time as we wanted and left us looking forward to getting back on the water.

Having learned a lesson from our last first Owyhee attempt, we had decided to go with inflatable kayaks (IKs) instead of canoes. Light and forgiving, we figured the larger tandem models would allow adequate provision for gear. I read recently that 600 cfs is the minimum recommended flow for IKs, but with a little walking and lining of boats you can run in much less. Frankly, we were worried about ripping a boat from stem to stern in the middle of the canyon; that would bite deep. But, in the end, we needn’t have stressed; after an ungodly amount of draggage, it is hard now to even find a mar, much less a tear, on the bottom of any of the boats. The fabric on all the inflatables we’ve run over the years, from PVC to coated nylon to Pennell Orca, has proven solid. For that initial IK adventure, we brought a beamy 13’ Saturn that seemed a good fit, and I tried a 17’ IK that caused more trouble with maneuvering issues than I gained from the additional hundred pounds of burden. Otherwise, the trip went well in all respects.

After our two initial trips through the canyon, we felt like we had an optimal game plan dialed in: we’d run bomber two-person self-bailing IKs (paddled solo) and spend two nights in each of our favorite bits of canyon, with a third camp TBD. The conservative half of my “think radical, act conservative” approach reads a little differently on a trip like this than on the remote seacoasts which inspired it. We still prepare for injury and death, but the risks are not so much dangerous as discomforting. Yes, you could potentially flip/pin/drown here in 100 cfs in a perfect storm, but a more likely source of trouble would be a serious injury that required an emergency response. We typically carry a SPOT to cover that base, and we carry portable radios, particularly when hiking alone. Otherwise, it’s gut it out as best you can with injuries, which are easy to come by when you’re messing around in a rocky canyon. Largely what we are conserving on a trip like this is our well-being, which means staying ahead of nagging everyday concerns like sunburn, blisters and dehydration.

Over the long winter months and into early spring 2012, we talked up the fall trip with our friends. It was easy to convey the upside of the place, especially from our photographs. The river and canyon are stunning beyond words. As for the risks, we saw it mostly as very hands on with lots of physical effort and decision making, but not so dangerous that we wouldn’t bring a newbie. We would take a full week and run the same 30 miles. We had a pretty good idea who was interested. We picked up Steven Wrubleski, an old back-to-the-land artist and permaculture farmer who had been down the O’ a couple of times and loved it. We had Robyn Minkler, IT wizard and veteran cameraman who’d been down many such trips and always had a smile on his face. Moore Huffman would fly up from LA where he worked as a musician and recording engineer. (Moore brought conventional creek boat expertise and would run his hard shell.) Steve Thomsen, our engineer and vet guy on these kind of trips, signed up too, leaving one seat left for a cook.

We typically bring a cook on river trips, as the freedom they afford the team is priceless. There is usually someone on the island here that cooks like a demon and would love to come along, but maybe they’re short on cash. We’ve had lots of male cooks over the years, but in the last five years or so it’s been women: Dawn Rachel, our Dutch-oven Diva and a fishing machine for most of that time, and now we’ve got Callie. Callie is a unique individual, in her early twenties, a neo-hippy, forward thinking activist and bearcat. The popular “Knowledge Share’ community program she co-founded here in the islands links up older wisdom with sustainable paradigms. When I asked her if it was the kind of thing she might like to do, she lit up like a gas fire:

“Hell yeah!” she said, “Are you serious?”

Nothing to think about there, no matter she’d never run a river before. She was in like a draft through a broken window. You know you’ve got the right people along when it feels so right in their soul that they are instantly, 100% on board. Your mileage may vary with this depending who you hang with, of course, but we are fortunate to have an outdoorsy, head-screwed-on-straighter-than-most pool to choose from in our counter-cultural island milieu. Huzzah!

By late summer we were getting antsy. Each of us had our own agenda for our time time in the canyon, some more accoutrement intensive than others: shotguns, vests and shells for hunting, fly rods, reels and tackle for fishing. Cameras, lenses, tripods, and big Pelicases to protect them. Rock hounds would start out light and end up anything but. We had discs for disc golf, but they were light and easy to tuck in the corners of the boat. We had group gear like portable tables and beach chairs, a gravity-feed water filtration system, a ton of Clif Bars and Gels, all the food that we divided up and labeled in see-through Ricksacks, a Dutch oven and a small sound system. And, let us not forget, plenty of beer and single malt, plus a choice bottle of red or white to complement Cajun pan-fried chukar and Jack Rabbit cacciatore.

About a month out, we checked the extended weather forecast for Jordan Valley for the first time. An absolute wall of heavy rain was predicted for the week we were there! Such that we were kicking around ideas for contingencies in case it all went to hell. I can tell you that a week of cold rainy gray weather and wet, sandy equipment was not the kind of “radical” we had in mind. Then I got a link from Steve to the USGS flow graph for the river. Whoaa. Record low cfs looming. It was down to 60 cfs at one point not far from launch. Prior trips had been at around 150, and it was frankly hard to imagine it much lower. But there is nothing you can do when you plan this far ahead except have a contingency plan in place and cross your fingers.

A couple of weeks out, our fingers still crossed, we had all the boats lined up and nearly all the logistics settled. Now it was just a matter of getting there and back. There was no way around taking three rigs, not all of which were capable of making the final descent into the canyon. From the rim, we would shuttle or hike everything down, then leave the rigs all lined up on the top for Marvin, the shuttle driver. We’d gotten to like friendly, old timey Marvin over the years. He was the kind of person that reaffirmed one’s faith in humanity.

And with faith in our plan, we counted down the days.