I was at the bottom of a canyon in West Texas, getting sandblasted by 40 mph winds when I first heard about the crew being formed. New to Terlingua, I had been invited to join the season finale float through some of the more remote parts of the Rio Grande with a handful of other guides. We had just finished a gritty dinner and were waiting for the dishwater to heat when I heard some of the other boaters chatting about their upcoming twenty-eight day Grand trip. Three of them, a set of twins and their best friend, were TL’ing a trip that launched February 9th.

The Colorado sets itself apart in the river community due to its moody behavior, raw power and depth of lore—a reminder of the golden age of guiding when whitewater was an endless series of mysteries for an oarsman to solve and resolve. A place where some of the most outrageous stories in river running history originated, passed down guide to guide whether in humor or warning.

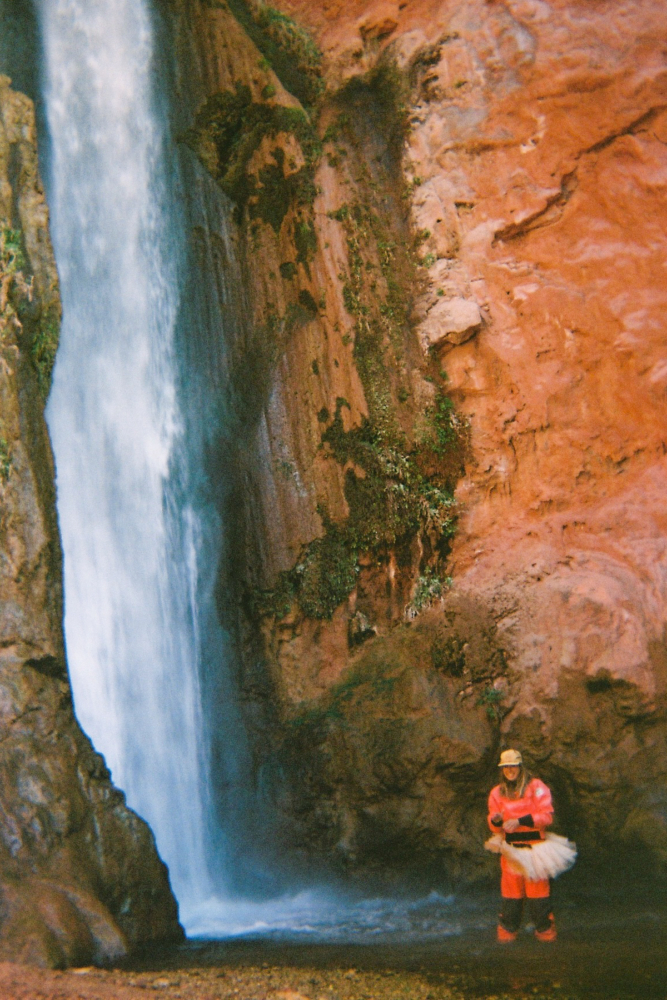

I had read about the canyon with the same devotion others might reserve for prayer. My copy of Kevin Fedarko’s The Emerald Mile had dog-eared corners, my favorite passages underlined, starred and highlighted. In Fedarko’s hands, the river felt alive, its breath matching that of the oarsmen who moved within it. In true river rat fashion, I was obsessed with the thought of testing my skill set against the canyon and pointedly told them that if they needed another oarsman, I was available. And thus, my journey from the Rio Grande to The Grand began.

Grand Canyon winter trips encompass a special set of circumstances rarely found in other downriver trips. An equation whose obscure formula, made up of ((length of trip^layover days) – commercial floats +/- weather) whitewater), has the power to create a self-contained community below the rim. It is improbable for a boater to spend twenty eight days with a set group and not feel the door of vulnerability being repeatedly nudged open by the universe.

Our crew consisted of 16 outdoor guides. NOLS instructors, river guides, canoe and backpacking guides; others worked for national parks or the forest service. While most of the group was meeting for the first time, our universe threads were woven together long before we actually entered the canyon.

The anticipation of being off the professional clock and on a lifetime trip elevated the excitement and intrigue as we offered up introductions and safety certifications over couch beers. For myself and a few others, this would be our first winter Grand trip; all of us silently running over our pack list as we compared gear loads with the more seasoned boaters.

As customary for rig day, we floated a short way down to camp for the evening. Crawling in my sleeping bag that night, the reality of a twenty-eight day trip settled over me; Would I have the mental and physical strength required to run the two hundred and eighty mile stretch with a group of strangers? Would four weeks of being exposed to the elements, cut off from routine and comfort finally push me to a breaking point?

There are often moments of fear and doubt when an individual stands on the precipice of something that stretches and refines who they are. Even as someone who is constantly walking the metaphorical cliff edge, I felt more like Icarus than Grua in that quiet moment, silently bargaining with the universe for a golden run.

The first week proved to be a refining period as we navigated freezing temperatures and snow* while adjusting to cook crew rotations, camp setup and group dynamics. This was a pivotal time for the crew—nothing brings people together like mutual suffering while huddled under a river wing. Maybe those first days helped to break down our barriers, the conditions encouraging us to let each other in as a source of physical and spiritual warmth.

A couple days later at upper Nankoweap, we were crowded shoulder to shoulder around the campfire when someone posed our first group question, “What is something that has shaped you that may not be obvious to others?” I was pleasantly shocked by how open people were, the effortless way we held space for each other’s stories. That night, I wrote in my river journal, detailing how one person’s vulnerability opened the door for others.

Nakoweap

Many sharing stories of difficult family life, big career changes, divorce, death and a deep love for the wilderness. A common thread of returning to the wilderness as an active choice of healing and peace. It brought me to tears in a good way and solidified the stories that I want to tell- the struggle – I am on the right path.

By day nine our group had successfully navigated our first handful of real rapids, including House Rock, The Roaring Twenties, Horns and Hance. We had developed a routine: scout, cheer at the top of our lungs for the kayak lines, then hustle back down to the boats to shuttle all the gear rafts through.

Staring down horizon line after horizon line, gripping the oars and pushing with my full weight against both wind and water while my crew cheered, felt like transcendence. In those moments, I understood what Fedarko meant when he wrote: “Any one of those rapids could also transport you into a dimension of pure, unadulterated joy that had no analogue in any other part of your life.”

This positive energy carried over as variables for our “perfect trip” formula began to materialize: comfortable camps, sunny warm weather and clean lines. Meditating on the rocks at Granite, I considered how the river may be the same entity to everyone on a physical level, but the metaphysical layer was a complex dynamic that shape shifted, dependent on the individual and the way they moved through the world. The way the river and canyon held us was the practice of Kintsugi in motion. It was repairing the cracks in our soul, excavating, shapeshifting, molding with astounding force until the person before is unrecognizable.

It is not an easy transformation. After two weeks the entire group was feeling the impact of exposure and rawness that accompanies living on the river.

Prior to launch, a friend and canyon guide had warned me to expect an existential crisis mid-way through the trip. Somewhere between Day 11-15, he cautioned, one might feel out of touch with reality, cry a bit and question what they were doing with their life. I had laughed at him, but he was correct. I was witnessing a subtle transformation in myself and others in real time. And as I watched this inescapable tidal wave encompass every member of the group, the ways it softened, extracted and replenished, I witnessed the freedom given to be one’s full self. A type of surrendering.

Matkat Camp

We are barely half way through and I feel so exposed emotionally and physically. I hadn’t anticipated the way grief and vulnerability would show up; I’m constantly being challenged by the depth of conversations I am having. Many share their deep love of whitewater, but also a deep sense of being “the other” in the outside world. I’ve been intrigued at some of their responses and descriptions to questions about running the river – everyone coming from varied perspectives yet still fulfilled. It again points to the metaphysical metamorphosis that can take place on a river trip. An invisible uniting of universe threads that weave deep networks of connection beneath the surface.”

***

We began to fall into a comfortable pattern as we entered week three. Each morning the rotating cook crew started their duties with cowboy coffee**, all of us favoring our slower layover day mornings (our twenty-eight day trip had eleven layover days). At this point we were running big whitewater almost every river day, all of us anticipating Lava Falls. By a twist of fate, most of our bigger lines were occurring at the same time as high tide. A quiet excitement thrummed as all of us considered how Lava would materialize.

Tuckup Camp, Night before Lava

Lava is tomorrow. I’ve been waiting for this thirty seconds for the last nineteen days. Up until this point I’ve felt evenly matched in my physical and mental skill set, but I’m walking a tight line of who is actually in control when it comes down to me vs the full might of the river. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t scared; then I think, that’s actually the entire point of a river trip. To push the limits of your capabilities, the boundaries of what scares you. The doing of the thing, regardless of fear.

For those who are new to whitewater, allow me to explain a bit about the dynamic between whitewater and an oarsman. Grand Canyon whitewater is plentiful, has large CFS flows and a dynamic variety of features. The beta for most rapids follows a similar formula. Enter centered up to your line or cross current ferry, square up to opening laterals, avoid one or two mean looking holes, finish out with a couple standing waves. A special few, Crystal, Lava, Hance, etc., double your risk due to their length, multiple pin features or varied sets of obstacle waves stacked closely together. They are legendary for their features and their potential to upset even the most skilled of oarsmans. But the real magnetic pull of these rapids are the lore behind each one.

There is a feeling when you run these lines, as if you are reaching your hand into a metaphysical river composed of every every oar stroke ever taken, of the hope, fear and joy experienced. Above the big rapids, the veil is the thinnest. Those are the moments when you can feel the older generations urging you downstream. You can hear boat captains—past and present— talking themselves through the sequence of moves that will transport them into euphoria. And no rapid quite embodies this sensation like Lava Falls.

Our luck held as the entire crew made it through Lava without swimming (despite a very dicey run on my part), and upheld the traditions of Tequila beach in celebration of one hundred and seventy-nine miles done. After roughly thirty consequential rapids in the last twenty days, we had witnessed one another in our strongest and weakest moments.

Sitting on the beach, I looked around at the people who had become very dear friends, all skilled boaters who were not only talented, but warm, inclusive and kind. Deep gratitude—the kind that makes your throat tight and nose burn—overwhelmed me as I sat in the realization we would never be here, like this, again.

As we floated our final mileage to the take-out, I reflected on the past month. As a guide, I spend a lot of time living on the river, but twenty-eight days had pushed my boundaries of comfort and self. Running some of those bigger rapids forced me to consider why I run whitewater. Why I’m willing to spend months away from people, a comfortable bed, a “normal” routine, in pursuit of this metaphorical high that only occurs when I think I’m going to pee my pants out of fear at the top of a rapid.

I’ve realized it comes down to the fact that for a small amount of time, there is an energy, a force meeting me toe to toe on the line. Navigating the dichotomy between fear and ecstasy, the way both can be within reach in the space of an oar stroke, there is finally something to test and break myself against.

The canyon had changed how I viewed myself, but it wasn’t the river’s doing alone. It was my friends and their thoughtful support, the lessons my ego learned about whitewater, the reminder that there is community in vulnerability. How, perfect lines or not, when you face the unknown in such a deep way, you join a legacy.

***

Guest contributor Alyssa Adcock grew up in the southeast river community, running whitewater and chasing wild brook and rainbow trout in the small streams around Asheville, North Carolina. Her love for the river and fly fishing led her to Appalachian State University, where she dove headfirst into the local angling community—serving as president of the App State Fly Fishing Club, volunteering on the High Country Trout Unlimited board, and working at a local guide service. Today, Alyssa guides full-time, splitting seasons between Montana, Texas and Idaho. When she’s not guiding, Alyssa is likely to be found studying river ecology, spotting migratory birds or camped out on her paco pad with a good book. Follow her adventures: @lyss_0202.

Footnotes

*What we would later recognized as one of three bad weather days in the entire twenty-eight day river trip. True nirvana.

**We made cowboy coffee almost every morning, until somewhere around day twenty-two or twenty-three, when one of the other boaters finally found the coffee sock.

References

Fedarko, Kevin. The Emerald Mile. Simon & Schuster, Inc, 2013