An impulsive “yes” flew me into Grand Junction for a free rafting trip down the Gates of Lodore with a group of women veterans whom I had never met. Anyone who has done an overnight trip like this knows that the group dynamic is crucial to the emotional and physical success of such a trip. Going with strangers was a gamble, but it was a crapshoot I was willing to take.

I was coming up out of the muck and horrors of Hurricane Helene, when the creeks and rivers of Western North Carolina swelled to unfathomable levels, surging, sweeping and swallowing everything that had been carefully planted over a hundred years. My newly-built alternative therapy retreat center hadn’t even held its first class when the North Toe River rose from 1,000 CFS to 163,000 CFS. Only chunks of two concrete posts remained in the decimated and rocky bank. Once a quarter mile of lush grasses with ancient oaks and sycamores—all gone. My neighbors’ houses, gone. One neighbor is still missing, his house washed away and splintered into pieces with him in it.

At first, I felt betrayed by that river. I often spent my evenings paddling into the sunset with a vodka spritzer, walking the gravel road along the railroad tracks back upriver, serenaded by newly born peepers across the swinging bridge and up my driveway. I bought my boys duckies and taught them to read water. We fished, we swam. We swung from ropes and picnicked along her lush banks.

Within 24 hours of the first rains, those banks reassembled into a harsh, rocky escarpment more apocalyptic than idyllic. There were no bridges, the railroad tracks felt like an abandoned funhouse, littered with drowned trout and smallmouth bass.

After helping people get supplies and resources to survive, I was ready for a breather. I wanted scenery devoid of abandoned, boarded homes, and rivers full of twisted metal remnants. I needed to step away from the devastation and trauma, to bandage my grief. But it felt wrong to leave my river people. I have always reached for the river for equal depths of peace and excitement. Yet for eight months, I could not pull myself away from helping put it back.

This would be the first time Philip and Kathleen Crowley of Veteran Excursions offered a veterans trip for just women. All 10 of us piled excitedly into the Airbnb in Grand Junction, sifting through perfectly packed camping gear and schwag. Meals were planned, our shuttle vehicles ready. We had everything we needed. Except fruits and vegetables, which meant lighter groovers and the opportunity to bond over intestinal bloat. A surefire shortcut to deep camaraderie.

Our group had a wide mix of river experiences, ages and abilities. One woman’s wheelchair had us scratching our heads for how to best get her and her trusty chair downstream. Being an excitable problem-solver, I quickly offered to piggy-back her at any time. She was remarkably resilient with a great sense of humor, and we ended up choosing to leave the wheelchair behind. Thankfully, we never needed to drag her through the sand.

Her adventure buddy, Gail, was a 72-year-old Vietnam Air Force Vet with a can-do attitude and a rare spinal disease. Her desire to participate in everything meant there were at least two of us assisting her at all times. Each morning we’d prop her up on the bow with a broad hat, a creek chair and layers with her cane strapped nearby for hikes and handles to grip through the rapids, in which she joyously yee-hawed. She experienced her first-ever river beer, a PBR of course. Gail giggled learning how to “shake her taint,” and every day she begged to help on the oars.

Our mascot, brought by our “river doctor,” was an inflatable dinosaur tube named Lodora. Gail let us lower her into Lodora so our safety kayaker could pull her around on a leash while she sang God Bless America.

The river was crystal green with soaring cliffs of granite, sandstone and iron ore. We slipped into the canyon and immediately felt serenity tinged with the excitement of a new place and new friends. At the confluence of the Yampa, the headwinds hit so hard we doubled up on the oars and cussed our mothers, choking down gritty sandwiches in the blazing sun on a narrow bank as we waited for the winds to die down.

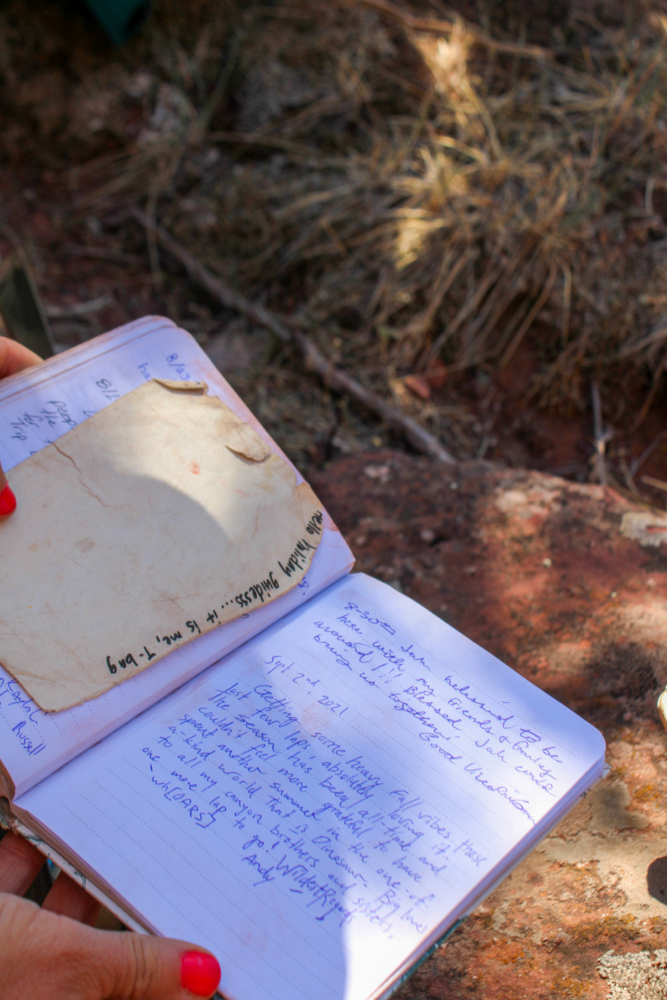

Our guide, River Betty (aka Jenny), grew up rowing these rivers. Jenny was a beast on the oars with a plethora of history and river knowledge. She brought us to hidden guide boxes filled with trinkets and notepads, pointing out ancient tools, petroglyphs and hidden waterfalls along breathtaking creeks and trails that made me pine for a fly rod. Then, she told us of the politics behind the desire to dam these rivers, which gave me even more appreciation for the political work done to save such a beautiful place.

We slid through steep iron walls with the sun sparking diamonds on the surface of quiet green pools of solitude. Tiny grottos marked the corners of turns where I imagined sitting alone with a journal. Jenny showed us the spot where a year prior she found and retrieved the body of a rafter who chose to paddle alone without a PFD. She choked on the story of pulling him from the water, recounting how she had created a landing spot for the helicopter and put him in the bodybag. The trauma left her speechless for hours. Later, she arrived home only to learn that her husband of ten years had moved out.

The river will always bring us to our core.

Jenny filled our evening circles with stories and laughter as we shared the excitement of our days. She scouted the rapids with us in tow, explaining how when she was seven, she took such-and-such line in her kayak and why that did not turn out well. Much later, Jenny made a mistake on that same rapid, flipping a raft full of custies. Her dad knew about it before she reached the take-out, calling for a meeting in which he drew pictures of “why we don’t take that line.”

Most of us took turns on the oars, navigating fun rapids under the watchful eyes of bighorn sheep, eagles, trout, heron and deer. We cooked for each other, skinny-dipped before rose-colored ranges. Ran naked through camp for cocktails and then again for coffee. Jeered at the men paddling past our camp and asked if they were lost. We used all of our skills: counselor, hiking guide, yoga instructor, massage therapist, cheerleader, cook, story-teller, calming-the-heck-down manager, bartender and barista. At night, we found our tents early, only to rise at 1 a.m. to admire the star-spangled nights.

Despite running from trauma and the desire to cleanse my wounds with solitude, river water, the bones of the West, and laughter, I soon realized that we all came together with, and in, trauma, be it abusive relationships, degrading military men, neglectful parents, narcissistic siblings, war, illness and the pain of regretful mistakes.

With our newly-formed tribe, we held space for each other pushing boundaries. We were patient—we adapted and built strength, learning new things with our bodies and our minds. We let go of expectations for our individual outcomes. Instead, we took care of each other, reveling in the salve of being seen without judgement.

With our newly-formed tribe, we held space for each other pushing boundaries. We were patient—we adapted and built strength, learning new things with our bodies and our minds. We let go of expectations for our individual outcomes. Instead, we took care of each other, reveling in the salve of being seen without judgement.

Every one of us was all-in.

Those days on the Lodore, I didn’t leave my trauma or resolve my grief in letting it go. Instead, I let it in as fast and deep as it has flowed for eons, learning how to see its gifts. And then I added to it. By opening myself for the trauma of these women and sharing in it, it became less powerful and controlling, rising and receding like the rivers that brought us together.

***

Guest Contributor Bettina Freese lives on the North Toe River in Appalachian North Carolina. Says Bettina, “I knew I was destined for whitewater the first time I put a canoe onto the Eno River. Part of the crew dumped our fried chicken and dry clothes into the river after wrapping a rented aluminum boat around a boulder. It was one of the best days ever.” You can find more of her work at https://bettinafreese.substack.com/.