It’s not that I’m not afraid of the dark. For a long time, I measured how my life was going by whether or not I knew the current phase of the moon, a check to see how often I was sleeping under the stars or hiking home after sunset, sucking the marrow of each day in through my teeth.

But something about paddling after sunset always felt a little unhinged. Raft guides used to rally for full moon runs back in the day. It always sounded beautiful, just enough eerie light to guide you to the smooth V-wave passages between cresting waves and crashing holes. I never joined. The excitement around the runs felt like the wrong kind of wild, almost frenetic. It was party energy, and it wasn’t for me.

Years later, a pandemic-era move to Maine delivered me to a wee seaside shanty of a guide shack stocked with star maps and glow-in-the-dark souvenir t-shirts—home to Castine Kayaks. I’d been looking for guidance, a way to explore Maine’s frigid waters, colossal tides and broken, confusing coastline. Karen Francoeur, the owner of the shop and a local fairy guide mother, offered a solution. Her annual sea kayak guiding course started the next day, and I signed up on the spot.

In Maine, wilderness guides have to pass a pretty rigorous testing protocol and register with the state. While a formal class isn’t required, it certainly improves your odds of passing the first time around. For a week we worked on reading the weather, plotting and navigating courses that account for tides and currents, packing for overnight expeditions and towing each other around Castine and Stonington. While learning to maneuver the 16-odd feet of a sea kayak felt surprisingly awkward compared to the whitewater boats I was used to, it felt good to be out on the water.

I passed the test, and Karen offered me a job. The thing is, Castine Harbor is a bioluminescent bay, and Castine Kayaks is best known for guiding clients through these otherworldly glowing waters—at night.

I mean, it’s an odd thing to complain about, landing the spectacular opportunity to experience a rarely seen miracle of nature on the clock. And Karen has refined a process for training new guides in the distinct art of leading tours in the dark: you shadow an experienced guide for as long as you need to. This is especially wise since the glittering bioluminescent solar systems and comet trails that each paddle stroke conjures tend to distract you from concentrating on your customers.

Bioluminescence occurs in oceans around the world, but it’s rare for it to appear consistently, night after night, in the same place. Karen has run tours in Castine for 25 years and paddles there year-round. She’s never seen a night when the water didn’t shimmer.

The sparkling swirls are created by dinoflagellates, a category of mostly single-cell planktonic organisms known as protists. They’re neither plant, animal nor fungus, but something else entirely. Some species eat other organisms, some photosynthesize and some, known as mixotrophs, do a little of both. These are the tiny creatures that light up bioluminescent bays around the world, including Luminous Lagoon in Jamaica, Bio Bay in the Cayman Islands and Mosquito Bay, Laguna Grande and La Parguera in Puerto Rico.

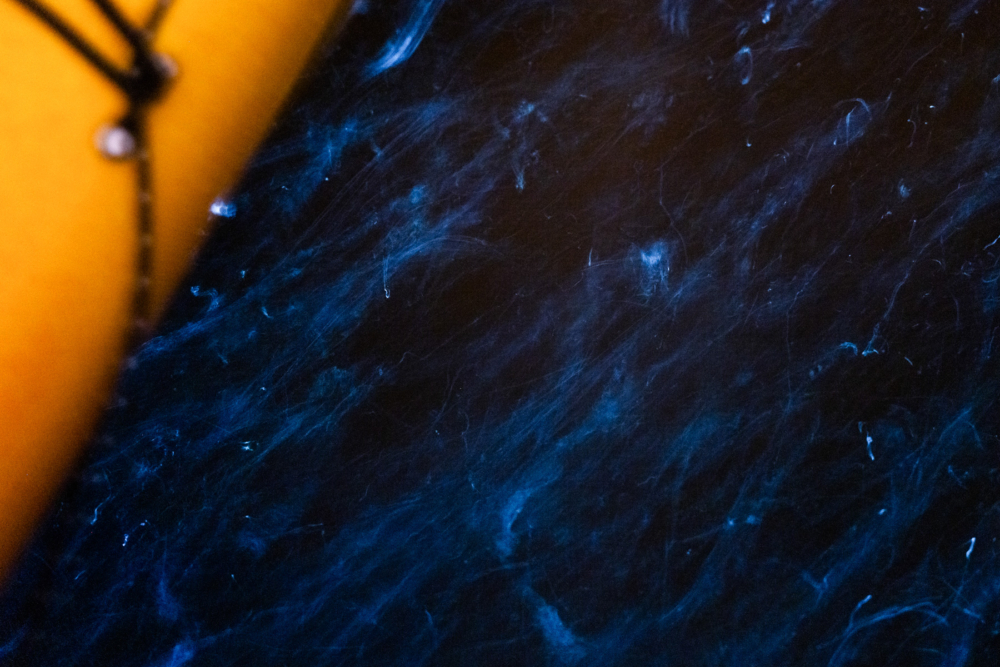

Those who have visited bio bays in those warm, equatorial waters and then traveled to Castine report a marked difference in the character of the phenomena. In the tropics, there is a diffuse glow that emanates from every disturbance in the water, one that envelops you if you jump in for a swim. In Castine, the biogenic light manifests as distinct, individual lights, twinkling like paddle-activated lightning bugs. (Plus, the water is often too cold to make swimming very practical.)

The difference may arise because the species in cold-water Castine are larger than those in the tropical bays, and less concentrated. The warmer waters likely support higher densities of dinoflagellates that are more metabolically active, resulting in a longer or brighter glow. No one really knows, because no one has studied the waters of Castine. That’s changing this year. Guide and student Emma Archambault is working to confirm which species of microorganisms light up the night in Maine’s dark waters.

We do know that, like lightning bugs, the luminescence of these plankton arises from the combination of luciferin molecules and oxygen, as facilitated by the catalyst luciferase. When oxygen steals electrons from luciferin, it gains energy. To return to a stable state, it must release this frenetic energy in the form of light. (On many days, I wish I could do the same.)

The difference between the plankton and the lightning bugs is that the latter can control this interaction using an organ whimsically called a lantern, resulting in their distinctive blinking patterns. The dinoflagellates have less agency. When you smash them into oxygen molecules with the stroke of a paddle blade, they can’t help but burst into spiraling displays of blue-green light, birthing galaxies with every stroke.

The result is stunning. Sometimes each light is large and distinct, gleaming aloof in the water like the North Star. On other days, often after a rainstorm, they’re minuscule and plentiful, creating a mat of undulating light on the water, a miniature Milky Way. These are my favorite displays, when we coach our clients to paddle hard and gain speed before rocking their boats gently side to side. Comet trails of liquid starlight shoot out from the bow, bending your perception with startling effectiveness and warping your world to lightspeed.

And that’s just what’s happening below you. Wait until you look up.

Rural Maine has less light pollution than most areas on the East Coast, boasting some of the darkest skies east of the Mississippi. As a result, I’m often torn between marveling at the miracles unfurling beneath my boat and the infinitesimally detailed universe spilling across the sky above. Amidst this otherworldly splendor, I’m supposed to be guiding.

We attach red lights to every boat to keep track of them without ruining our night vision. During my first few tours, I would obsessively count each one, making sure that no one lagged behind, lost in the incandescent splendor. Gradually, those counts became second nature and took up less of my mental space. I was able to answer questions, offer guidance and plan our next moves more seamlessly.

Just as I slowly learned to map the stars, pointing out the epic mythology unspooling in the heavens during our mid-paddle astronomy tour, I began to map out the contours of the bay in my mind. Still, I was reluctant to lead night tours on my own. Since I worked several other day jobs and was rarely able to paddle the harbor in the daytime to learn its nooks and nuances, this process took longer than expected.

It wasn’t until my third season guiding that I was alone on the water with a group of paddlers. The trouble was, that night happened to be an exceptionally low tide, giving us precious little room to work with in my favorite cove without accidentally stranding the group on a sandbar as the water rushed away beneath us. The bioluminescence is brightest when you first disturb it. As we lingered, the water, and the group’s enthusiasm, dimmed with every paddle stroke, but there wasn’t enough room or time for us to venture to fresh waters.

The previously cloudy sky opened up just enough to toss me a lifeline. I pulled the boats together in a raft, allowing everyone to relax as I pointed out the constellations. Cygnus the swan flying high in the sky through the summer triangle. Cassiopeia, seething in her vanity and exile beside her husband, Cepheus. Their daughter, Andromeda, forever chained and waiting for nearby Perseus to save her from the sea monster, Cetus. Halfway through, the laser pointer we use to chart the stars died. Flustered, I did my best to talk through the zodiac signs that wrap around the horizon, ending with my favorite, Sagittarius, the tea kettle whose trail of steam swirls across the sky to create the Milky Way.

Throughout the tour, the outermost boats paddled slowly, spinning us in a circle until we were back where we began—but the sky had changed. I gasped. Above us, a massive swath of sky smoldered flame orange. It was Aurora Borealis, the Northern Lights, and it had swallowed the Big Dipper whole. The auroras had been more common that summer, with iPhones capturing vivid displays in the weeks prior, but this was the first display I’d been lucky enough to catch. We floated in awed silence for around ten minutes, until they abruptly faded from view.

Persistence and patience are often rewarded. Mine felt exalted that night. For all its challenges, navigating in the dark offers insights into ancient relationships with our world. Light from the stars allowed our ancestors to cross oceans, and dark skies are essential for the successful migration of animals like sea turtles and birds.

Artificial light blinds us to many of our world’s greatest gifts, to our literal place in the universe. I knew this when I was a kid, catching fireflies and dreading the autumnal return of Orion, signaling the end of summer.

Guiding night tours is helping me remember, reminding me to be brave enough to turn out the light.

***

Guest Contributor L. Clark Tate is a writer, audio producer, photographer, documentarian and registered Maine sea kayaking guide. Her work ranges from offshore windmills and white sharks to artists and adventurers who sacrifice for a meaningful life. Says Clark, “I can’t get enough of our world or the people in it and seek to share that sense of wonder in my work.” Find more of her work at lclarktate.com.