The following essay is an excerpt from Let The Water Do The Work, a memoir and history of whitewater rowing by Peter Fox.

***

First Raft Descent, Futaleufú River, Patagonia, Chile, 1985

A HARD RAIN HAS BEEN FALLING for days, but we catch a break enjoying the only hours of sunshine of the trip. Passing through level fields near the Argentine border in Chilean Patagonia the smooth current gives no hint that the Futaleufú River is in full flood. In the afternoon we make our one and only dry camp in a sandy cove where our passengers maintain their high spirits. After all the planning, travel, and expectations, they are finally launched on the adventure of a first descent. Our crew of three guides and outfitter, Steve Currey, do our part by preparing a feast, and as the sky darkens sparks from our campfire dance with unfamiliar southern stars.

It is on the second day that our dream of running an unknown river comes face to face with reality.

At the confluence of the Rió Espolón, three of our five Nantahala safety kayakers decide not to continue. They heft their boats to their shoulders and head back toward the road. As the Espolón pours additional volume into the Futaleufú we are left with two indispensable additions to our team, expert kayakers Kathy “KB” Medford and Eric Nies, their importance quickly becoming apparent when the river turns a blind corner into a high walled canyon. From their positions out in front of the rafts they disappear from sight, only to pop right back out paddling hard upstream along the right shoreline, windmilling their paddles to point us toward an eddy. We row to shore beaching our boats on sand that may never before have seen a human footprint.

Once they reach us, Eric and KB urge in strong but measured terms that we tie up and scout the canyon ahead. Around the corner they have seen whitewater exploding from where the river drops off below an abrupt horizon. The first meaningful decision of the trip has come faster than expected.

I remember what the canyon ahead looked like from our aerial scout the previous year. The rapids seemed straightforward enough that I’m ready to turn the corner and keep going. Steve, our boss, was home in the states when my guiding partner Danny Bolster and I scouted the river from the air. Steve turns our way, trusting us to make the call. Danny gives me a look.

Glancing at the thick undergrowth on the ridge thirty feet above us, I sigh. As the lead boat I am responsible for keeping us on schedule, and I feel the day slipping away. I know Danny is right. We should trust the kayakers and go take a look at what’s over that horizon, but with no sign of a trail, scouting will eat up hours we’ve been counting on to make miles downriver.

We have budgeted four days to cover the roughly thirty-five-mile length of the Futaleufú, a little over eight miles a day. A very reasonable amount of distance and time for the rivers we are used to running. Our twelve passengers have flights booked for the afternoon of the fifth day. By the end of today we should have covered sixteen miles. So far, we’ve done maybe half of that. But scouting is still the prudent thing to do. Grabbing my camera out of its ammo can, I follow the others up the slick slope into a dripping forest.

Slipping and squeezing through tightly packed trees and stands of bamboo, we reach a vantage point above cliffs that rise straight up out of the river along both banks. Without low lying shorelines, there is no more evidence here that the river is in flood stage than we saw in the flat running current upstream. The half mile canyon with a dogleg right-hand bend in the middle is undeniably spectacular. From above, we can see the exploding hole that caused KB and Eric to retreat, but also an alternative line of waves that looks reasonable as long as we don’t get surfed into the eddy at the dogleg.

I stop and pull up my Canon FTB while the others continue bushwhacking downstream. Through the compressed view of my 200mm lens I examine more waves at the bottom end of the canyon. They look big and some are collapsing back with piles of foam at their tops, but they are waves, not holes; nothing we haven’t run before.

Satisfied that Steve’s extra-large 22-foot rafts will handle them, I settle in while Danny, Brad, and Steve hack through another quarter mile of forest for a closer look. I capture them on film, tiny figures in red dry suits against a sea of green, Danny craning over the edge a hundred feet above the river doing his due diligence.

For a rapid that might take us five minutes to run, it has taken us three hours to scout, and the others have reached the same conclusion I have. In Steve’s boats we’ll be fine down there, and we will be, but not for the reasons we think. We are right about Steve’s boats. We are wrong about the river.

Back at the beach we load up and I row off shore making sure that everyone has cleared the eddy before following Eric and KB into a stretch of river that is now known as Inferno Canyon. Approaching the horizon line, I slip into strong current that will sweep my raft past the exploding hole and into the line of waves we scouted from above. I do not feel particularly scared. My adrenaline is running at a normal level. I aim at a spot on the horizon line in the last seconds before the river I have conjured in my head runs up against the reality of the flooding Futaleufú.

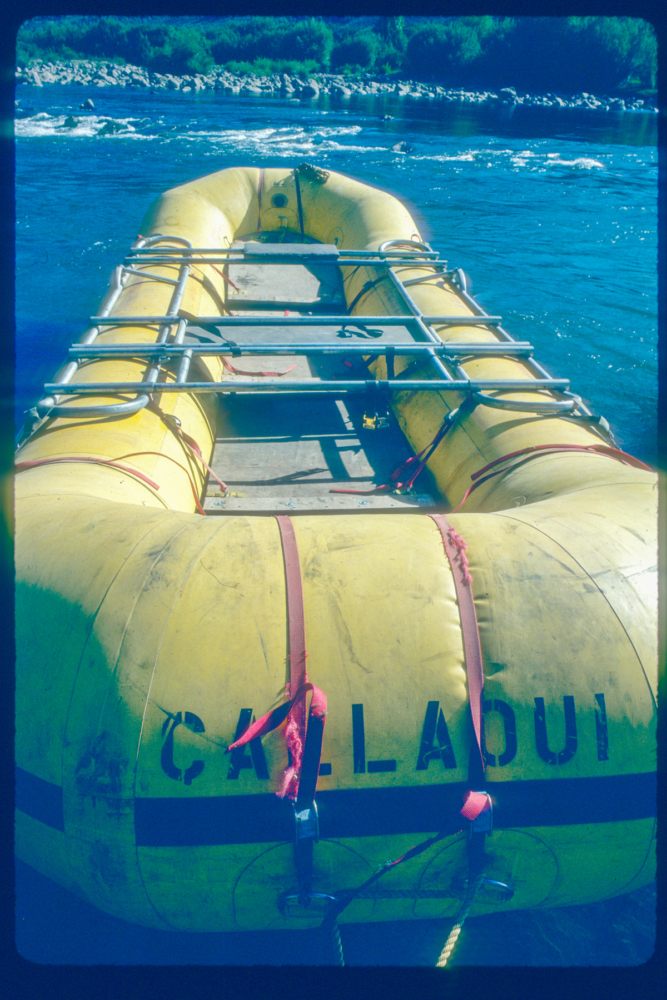

My raft, named the Cullaqui after a Chilean volcano, accelerates and drops over the lip. The wave that rises up in front of me is big but not huge. It looks like waves I have run before, but then we collide head on into an unforgiving surface, which feels less like water and more like crashing into the side of a building, and is definitively not like any wave I have ever felt before. Though a logical voice in my brain tells me this is impossible, my adrenaline jumps to full alert as I feel the same punch in the face sensation from every one of the waves above the dogleg turn in the canyon.

With no time to make sense of what just happened I cut the right-hand bend. In the brief let up, I spare a quick look over my shoulder to see Danny close behind, Brad Lord a little farther left, and Steve in line at the back. There is no place to stop along the sheer walls. I holler at my passengers to hold on and push hard toward the final white cresting waves. I’m not a small guy. I throw all 203 pounds of me into the oars, the Cullaqui absorbing a string of even stronger head-on collisions. Nothing has prepared me for this heavy weight pummeling. When the canyon finally spits me out at the bottom, I’m in shock.

Eric and KB stare at me wide-eyed from downstream. Danny and Steve come up behind and I register the same shocked expression on their faces. They have just come off a high water trip on the famously powerful Bio Bio River that failed to dish out anything like the pounding we have just taken from the much smaller Futaleufú.

We are all running the math in our heads scrambling to compute how a beautiful blue mountain river could punch so far above its weight class when Steve’s voice breaks into our thoughts. Upstream he saw Brad’s raft surfed into the eddy at the dogleg and it hasn’t come out. Our eyes turn back the way we have come. A tense minute ticks by, and then another and another before we finally see Brads’ bright yellow raft clear the dogleg and bash through the last waves, his momentum carrying him down to where we are waiting. Looking from face to face, he asks the question we have all been asking ourselves.

“What the fuck was that?”

“I don’t know,” says Steve, “Never felt anything like it.”

“Me either,” says Danny.

“Or me,” I add, the kayakers nodding their heads in agreement.

As unbelievable as it sounds at this distance, and as it sounded to us at the time, no one argues. We have been punched in the mouth by the most powerful hydraulics any of us have ever felt and we can make no sense of it. Steve has been guiding rafts since before he had a driver’s license. He has felt massive spring flood water on the Selway and the power of huge high water on the granddaddy Colorado. Brad has rowed his way out of the famous Forever Eddy on the Colorado, but in three tries he could not break out of the eddy in the first noteworthy rapid on the Futaleufú, escaping only after deputizing a passenger to take up one of the oars while he pulled on the other.

What if they hadn’t been able to get back into current? How would we have reached them at the bottom of a hundred foot cliff? I look at the thick forest crowding both banks of the river. We are completely on our own, cut off from the outside world on a river we have sorely underestimated.

When we scouted from the air a year ago, only one rapid caused Danny and me to ask the pilot to circle back for a second look—the one we know is now only a few miles ahead. From the airplane, we’d aimed our cameras through the windows of the banking six-seater at a Z-shaped channel carved through solid bedrock and choked with whitewater. At the time we believed the Futaleufú was going to be like other rivers we knew, so we hadn’t given the rapid too much thought. Now, the everything has changed.

Long before we see the ridge of bedrock extending three quarters of the way across the river from the right shore and hear the thunder of falling water, we steel ourselves for what is coming. The ridge rises in the middle like the back of a humpbacked whale, leaving only a narrow opening on the left side that squeezes down and concentrates the power of the Futaleufú like the nozzle of a fire hose. From the air Danny and I saw the narrow entrance and abrupt changes of direction of the Z. What we missed was the river dropping two stories off the edge of a cliff.

***

Read the rest of Peter’s descent of the Futalefú—and many more whitewater stories—in his book, Let the Water Do the Work, available for purchase at https://www.whitewaterrowing.com/ and Amazon.

—

Guest contributor and author Peter Fox trained as a river guide and fell in love with rowing rivers in 1980. In 1982 he led an historic high water descent of the Tuolumne River. Later, he was recruited by Sobek Expeditions and rowed on the highest water descent of Chile’s Bio Bio River in 1983. In 1985 he played lead roles in the first raft descent of the Futaleufú River in Chile, and on the Grand Canyon of the Stikine in British Columbia. Peter started teaching rowing in 1982, developing curriculum and leading Northwest Rafting Company downriver rowing schools from 2014 to 2023. A private boater since 1986, Peter is still rowing at age 72.