Between the sharp peaks of the Julian Alps and the Adriatic Sea’s Gulf of Trieste runs a stunning flow, carving one of the most beautiful valleys in the old continent…

The Soča River. An iconic waterway, worshipped by paddlers of all vessels. Unfortunately, most paddlers know only a few sections of this 138 km river. The romance of emerald whitewater and allure of simple shuttle means few have ventured further downstream than the town of Tolmin. But isn’t exploration part of what makes traveling by the power of a paddle so special?

One warm May morning, a curious crew of six set out to explore the Soča from source to sea, inspired by the making of the Soča from Source to Sea – Paddling Guidebook. A biologist who is a fisherman. A vegan who is a musician. A hunter who is an ornithologist. A photographer who is an alpinist. A videographer who is a foodie. And myself. Each of us saw the river from our own unique perspectives, the details of the guidebook and our real-life experiences combining to create a Soča River we never knew existed.

The following photo essay combines excerpts from the book and reflection from the team who created the book.

STARTING AT THE SOURCE

The source of a river is like the roots of a tree – hidden yet essential, providing the essence of everything downstream and anchoring the entire system to its origin. The Soča has two sources in Slovenia’s Julian Alps, one that is easy to access and one that is not.

The real, but less well-known and less spectacular (but therefore much more romantic) source is high in the mountains, where two geological layers meet underground and bring the waters of emerald beauty to the surface for a short time before sinking again into a thick layer of scree and gravel, which flow into such pristine alpine valleys. The journey to Soča’s true source, fittingly, is longer and more demanding, which is true to most good things in life.

“Even the drive to the parking lot was beautiful – the forest, the streams, the gravel road and traditional alpine-style houses, it was like being in the old Slovenian folk story ‘Kekec,’” recounts Branko, the musician. “All in the middle of nature surrounded by giant mountains. It just felt like everything was alive.”

We started our descent at the second source, where the water re-emerges as a karst spring from a limestone cave at an elevation of approximately 900 meters above sea level. The spring releases crystal-clear turquoise water that cascades down a rocky gorge before forming the river proper. It’s not hard to find, but it takes a bit of walking (and climbing) to reach. Even from the start, the Soča makes you work for her secrets.

ROCK SPLATS + REWARDS

The trail that follows the upper Soča is beautiful – a worthwhile adventure in its own right – but we were happy to slide off the rocks at Velika Korita and let the paddling begin. It seemed the Soča was also happy, delivering a gift some would consider a good omen for the trip ahead.

“We were doing rock splats when we spotted some beers floating in the river, bobbing around just under the surface,” says Bor, the hunter. “We saw one, two, three beers and we were stoked! Some more popped up and then Rok hauled out the whole flat of beer! We were fishing for beer for kilometers, finding them all the way down to Čezsoča!”

The uppermost paddleable section of the Soča River will captivate you with its diversity and beauty, offering everything from paddling over gravel beds and exploring narrow gorges to navigating rapids among large boulders, all under the majestic Julian Alps. On the right bank, you’ll see the Bavški Grintavec ridge with Svinjak peak, while the left bank is dominated by Krn with the Krnčica ridge. It’s the perfect stretch to start your journey towards the sea.

FLORA + FAUNA

After the village of Čezsoča, the valley opens up and the panorama of surrounding mountains warrants just leaning back in your boat and letting the water spin you to properly take it all in.

“I spend a lot of time looking down when I’m in my kayak,” says Rok. “The gin-clear water of the Soča means I can spot fish, and depending what section of river I’m paddling, different species of fish will be present.” Rok is a fly-fishing guide, biologist and founder of BRD. He wrote the guidebook, combining a passion for river conservation, a love of kayaking and a wish to help the river. Fostering an understanding of healthy river systems was an important component of the book, as was spelling out responsible river use by including tips for minimizing environmental impact, such as respecting fish spawning behaviour and avoiding bird nesting areas. Rok uses humour to illustrate these important points.

If you are too lazy to make a few extra strokes around the spawning pit of any of the Soča fishes, just think how you would feel if, during the most passionate moment of love-making, someone with a kayak on his shoulder walked through your bedroom and inadvertently smacked you on the head with a paddle.

BOOF VIBES

The book also features a section on river terminology, water levels, whitewater difficulty ratings and general river etiquette.

Boof – A paddling manoeuvre in which, at the edge of a feature or an obstacle in the water, you take a long stroke and, at the same time, lift your knees. When done correctly, part or most of the bottom of the kayak lifts off the water’s surface, allowing you to fly over a dangerous area of whitewater. This manoeuvre can also be used just for fun.

RIVER TRAFFIC JAMS

Of the entire Soča, the stretch from Čezsoča to Trnovo sees the most aquatic traffic. “It was important to the whole team to use the book to avoid contributing to over-tourism or environmental harm by dispersing paddling traffic,” says Rok.

The Soča’s commercial whitewater popularity in the peak of tourist season (July and August) often results in overcrowding, which puts pressure on the river’s ecosystem. By encouraging exploration in pre- and after-season, and of the entire river, the guidebook highlights lesser-known sections and helps relieve pressure on overused areas.

“If I compare the Soča Valley now to 20 years ago when I was coming here as a kid, it has changed for sure. I remember it was really wild, and that feeling has stuck with me, a strong memory associated with the river and region. Now it has grown in popularity and it’s not the same, but I still really enjoy time by the river and I really enjoyed exploring the Soča in a different way through the creation of this guidebook, getting off the beaten path.”

KATARAKT

If there is one place where you won’t find crowds, it’s in the Soča’s revered Katarakt section. Rightfully so, as it is a temple of sorts, for Slovenian whitewater lovers. Unfortunately, local politics has cast a dark shadow over ‘the gorge,’ forbidding paddling it, and adding steep fees to paddle the section of the river in the municipality of Kobarid.

The latest changes to the regulations (to a decree that was first accepted over 20 years ago) were adopted in 2024. The extreme increase in permit prices for paddling on the Soča in the municipalities of Bovec, Kobarid, and Tolmin caused a lot of justified discontent, leading to the regulations undergoing a constitutional review and were partly accepted and partly withheld. This guidebook does not list the currently valid prices and terms, as they will most likely change again in the next season. Each user of the guidebook is obliged to inquire about the current requirements, and, based on this, make a decision regarding compliance with them… Let this be another incentive to get to know the lesser-known parts of the Soča.

The Katarakt is one of the most respected parts of the Soča, in scenery, irascibility and the potential danger. “Each section has its own unique beauty – but the Katarakt is a bit untouchable,” says Branko. “To get the experience of paddling through it you have to really dedicate yourself to kayaking, and that way it remains inaccessible for many.”

This stage is reserved for only the best and most experienced kayakers, because in combination with countless enormous grey-white boulders and the beautiful emerald colour of the Soča, it is also home to innumerable undercuts and siphons, which have already been fatal for many experienced kayakers from all over the world. In other words, here it’s for real. This is a sequence of rapids of solid Class IV–V whitewater with Class VI consequences.

MELLOW OUT

Both the politics and the river calm down a bit after Kobarid with mellow whitewater, stunning vistas and time to birdwatch. Then, things calm down a bit too much thanks to the first dam on the Soča.

The Soča River, from its source to the sea, is cruelly cut by seven large dams and two weirs. Until 1905, this extraordinary river flowed freely, allowing the unhindered migration of fish species between the sea and the river as well as between different sections of the river.

“I would much rather photograph and film a river than a dam,” says Rožle Bregar, photographer for the guidebook. “The Soča before the dams is so beautiful – it’s natural and alive and has flow. The dams stop the flow and with it they stop the flow of colours and gradients. Rivers are of course more dynamic to photograph than something static like a dam, but it’s a challenge, in a good way.”

RESERVOIRS + RESIDENTS

Most whitewater paddlers are all but allergic to flatwater. But some people look for the silver linings, and Bor found birdwatching the best way to distract from the monotony of paddling the Soča’s reservoirs.

The upper course of the river, rich in mountains, often offers the chance to observe golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), or even a kettle of griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus), who fly daily from their colonies on the Croatian island of Cres and the cliffs above the Italian river Tagliamento in search of carrion among the peaks of the Soča Valley.

In the dammed sections of the middle Soča, the situation is different. Here, you can observe yellow-legged gulls (Larus michahellis), mute swans (Cygnus olor) and great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), all of which are species of lowland rivers and were not here before the construction of dams and the resulting reservoirs.

BORDER CROSSING BY BOAT

“As a Canadian who grew up paddling in the wide expanses of northern Ontario, it was pretty exotic to paddle across a border into a new country,” says Carmen, the author of this blog.

Of course, there are no borders in nature, but they are part of the nature of human society, so 130 metres downstream from the footbridge, when you see border stones on the banks, you can congratulate yourself on (legally) entering another country. In self-propelled vessels and without any formalities, this is a rarity even today and therefore an interesting experience. You are now officially on the Isonzo River.

The whole crew was shocked by how wild the Soča (now Isonzo) remains on its way to the sea, despite the dams. From the air, videographer Matic Oblak and Rožle got the heron’s-eye view of the river, noting how the braids and meanders – shaped by highwater events – restore habitat for water birds and vegetation.

The labyrinths of beautiful river channels, romantic meanders, and incredible views to the north from where you paddled and where the river flowed, make this stage truly special. In Europe, you can count on one hand the number of large rivers that remain crystal clear even in their lowland sections. The Soča, called the Isonzo here, is one of them and the only one that, in addition to the scent of the sea, offers an emerald hue.

“The Italian parts of the river are more influenced by dams, but there are some really nice sections of the river down there,” says Rožle. “It becomes wild again. I didn’t expect this in Italy and I’m happy we can show people that there are nice sections here too.”

Wild enough that fishing becomes an option again.

In fishing, there are specific fishing seasons and restrictions, including minimum allowable sizes for each species and, of course, limits on the number of fish you can take. Permits for the upper and middle stretches of the river are available at well-known hotels and campsites along the river.

SWEET OR SALTY

Even the sweetest songs have a final note, and the musician on the trip agrees. “We (Rok) planned to arrive at the sea when the tide was going out so the river was pushing us and the sea was pulling us,” he recounts. “There was no distinct line between the Soča and the sea, and although we were already well out from the river mouth, the water was still fresh (or sweet, as it is directly translated from Slovenian).”

“There was this moment of quiet, just floating and watching and admiring the confluence. Like a deep exhale with extreme happiness and some sadness too, because the trip was ending. All the experience took root inside us and that was the gift of the trip I think.”

Don’t be surprised if the water under your paddle suddenly becomes lighter and your speed slower. You have found yourself in the tidal zone, where salty seawater is pushed upstream by the tide. This dance of salty and fresh water reaches its peak twice a day, but you will find it more pleasant when the river takes the lead, as the pull of the tide will join its flow.

Eventually, the kayakers had to turn into the tide, the peaceful bubble of reflection popped by the need to paddle against the flow of the river to get back to the take-out. Soon, the joking and chatting resumed, as did plans for our next source-to-sea adventure.

***

Photography: Rožle Bregar and Rok Rozman

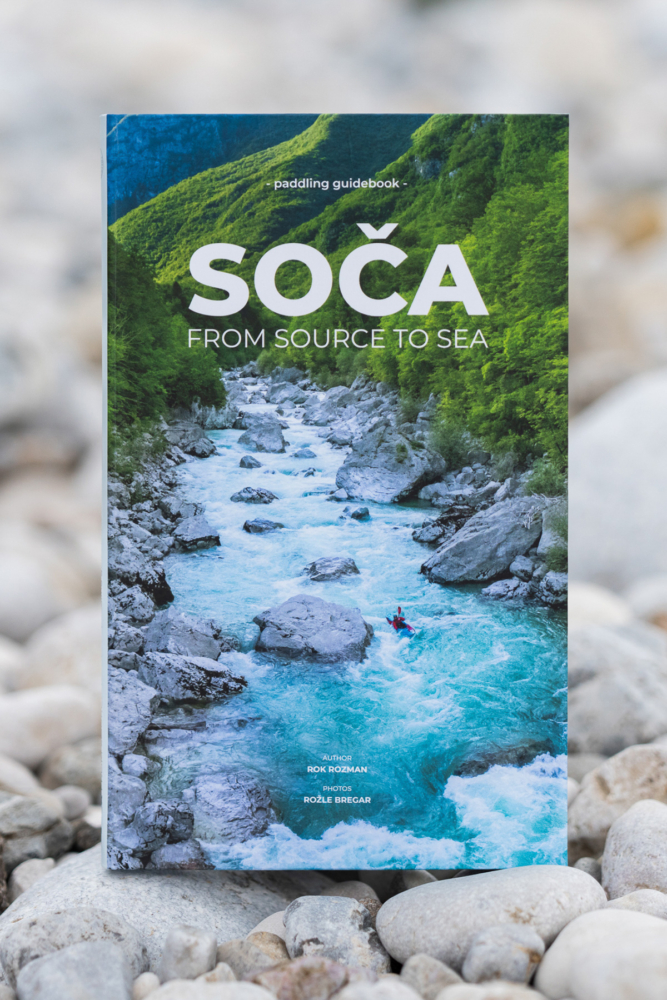

Editor’s Note: Leeway Collective, founders of the initiative Balkan River Defence (BRD), officially launched their Soča from Source to Sea – Paddling Guidebook in December 2024. Paddlers from Bulgaria to British Columbia have since cracked the cover of copies offered in three languages: English, Italian, and Slovenian. Its compact format (25 cm x 15 cm) makes it easy to stuff in a dry bag and bring along on the river yet is large enough to sit on your coffee table, a tantalizing reminder of adventures to come.

Buy your own or learn more: https://balkanriverdefence.org/soca-isonzo-eng/