Deep in rural Guatemala, expedition rafter Lacey Anderson employs a whiteboard and the common language of rivers to bridge the communication divide and train a group of indigenous Mayans to be river guides.

With a marker and small whiteboard in hand, I began illustrating hydrology to a group of Mayan Qéqchi´ river guide trainees. Their positive attitude and fun-loving ways felt familiar to me, even though I was deep in the heart of the Guatemalan jungle—these good vibes are common in the guiding industry. Standing on a dirt floor, in the entryway of a primitive plank wood house, I held up a tiny whiteboard to illustrate some river running principles to the young men who didn’t speak English, and whose native tongue was Qéqchi´. Grinning from ear to ear, I could see that these young recruits had many of the same traits as guides I had worked with closer to home.

So, how did I end up in rural Guatemala teaching indigenous Mayans to be river guides? As a person who has been involved with whitewater for over 25 years, many of those years as a professional guide, it was a natural extension of my passion for rivers. Like many guides, I enjoy new experiences that challenge my limits. It is this sense of adventure that has led me to rivers all over the western US, throughout Mexico, Peru, and Guatemala.

Through my connections (and guides usually have lots of connections!) in 2012 I was fortunate to join an experienced group of guides and river runners in an attempt to run the second descent of “the most beautiful river in Central America.” We never made it. The indigenous people, wary of outsiders potentially connected with mining or hydroelectric interests, detained us, and were prepared to kill us, to protect their river. Ironically, we were there to raise awareness of potential threats to the Rio Copon from a proposed dam.

Long story short, my friend Max risked his life, offering to stay with the villagers if they would release the rest of us. This self-sacrificing offer had a profound impact on me and the Mayans as well. The village leaders could see Max was an honorable and courageous man, so they let us go. That was not the end of our troubles that night, but without Max’s profoundly selfless act, we would not have survived. (Read about Lacey’s hostage adventure here.)

After the Guatemalan-hostage situation, I returned home to the States to process the experience, while Max remained in his homeland of Guatemala and started an NGO to help fight against dams and indigenous poverty. When he asked me to return to Guatemala last year to help with the training of a small group of villagers from Saquija, I, of course, agreed. He felt that with my guiding and teaching background, I would be a natural at training his prospective river guides for work on the Rio Lanquin and Rio Cahabon.

I knew it was going to be an interesting “guide school.” The potential guides were all local Qéqchi´ Mayans that spoke little Spanish and absolutely no English. I’m a native English speaker with a very basic grasp of the Spanish language. My fears of not being able to effectively communicate were eased when I met these fun-loving, adventure-seeking guide recruits. They emitted a very familiar air. I chalk it up to the fact that we had a common language: the love of rivers and the enjoyment that comes from being part of a team that looks out for each other.

Like many guide trainees, these guys were enthusiastic and ready to hit the river and start guiding, full of bravado and self-confidence, but lacking in basic guiding skills like raft control and swiftwater rescue. In order to become river guides, I would have to teach them the fundamentals, with little in common linguistically, but much in common through a desire to be on the river.

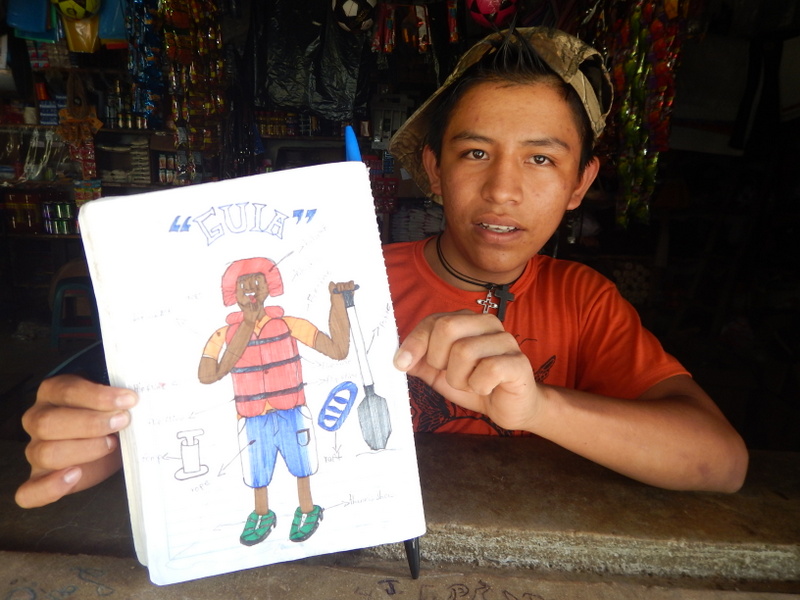

I began the first day of lessons with a crash course in English, since many of their customers would be English speakers. They were eager and prepared with notebooks to write down the new English language they were acquiring. Once a basic level of English was succeeded, we transitioned into the more fun side of guide school. I started by discussing what makes for a safe trip and then went on to discuss river guide equipment and safety apparel—rescue vests, river knives, proper river shoes, throw bags, and flip lines.

Being around the river and seeing the rapids and a few other boaters while they were growing up, they had some innate skills that would serve them well as guides. They were strong, passionate and courageous. They were attentive learners and quick to pick up on the safety aspects of being a guide. Throw bag practice was a popular activity and after my whiteboard drawings of pour-overs, holes, and other river hazards we walked down to the river to have a lesson in shoreline rapid scouting.

We tromped through the dense jungle to get a closer look at one of the rapids—considered a Class V due to the high water level—where we discussed how to safely run the rapid. They jokingly bantered back and forth at the site of this challenging rapid discussing how to run it with their newfound knowledge of rapid hydrology. This was a very familiar feeling; all guides love hanging out beside a rapid discussing the line!

When it was time to go practice on the river, I was confident that they had had enough book learning; it was time to start hands-on, on-the-water training. They made a surprising decision that increased my already high opinion of them to an even higher level. We were training during the middle of the rainy season. It rained every day and the rivers were flooding, running high and brown. They made the call to wait a few days to run the river because it was at a dangerous flow. I knew then they would not be just good, but excellent guides.

I was happy that they had internalized much of my lessons about safety and concern for the safety of others. It would have been a poor decision for our group of trainees, with only one trainer, to run a flooding river. By the end of our time together, they had a solid understanding of river hydrology and potential hazards; they had practiced lots of rafting skills, such as using throw bags and swimming whitewater. We also spent a lot of time doing raft flip drills, albeit in a pool. I think they are going to make great river guides because they now have some river skills to go along with their natural guide attributes like enthusiasm and adventure seeking.

Another characteristic of guides (and most river folks) is their passion for the river, the land, and the local people that depend on the river for their livelihood. One of the reasons I returned to this area of Guatemala is because the local river, like many others in Guatemala, is threatened by Guatemala’s desire for hydro-energy and the extensive clearing of the jungle for agriculture.

My hope is that commercial rafting on the Rio Cahabon will become very popular and provide a source of income for the local people, making it possible for them to supplement their traditional farming practices with eco-tourism. If so, the Rio Cahabon will be considered more valuable by the governing powers that be and further hydroelectric development may be halted. Like many guides I care about environmental issues and underprivileged populations. My caring has lead me to some unusual places and I love practicing what I preach with projects like this.

In spite of the language barrier and cultural differences I observed during my time in Guatemala, I found that the soon-to-be Mayan river guides were a lot like others I have come to know and respect in the guiding profession. They were enthusiastic, fun-loving, committed, caring, and courageous just like their northern counterparts. It seems to me that river guides are much the same, no matter where they are from.